Historically, libraries have been collections — books, multimedia materials and artwork. But increasingly they’re about connections, linking digital data in new and different ways, but Harvard Law’s Caselaw Access Project is a state-of-the-art example of that shift.

Harvard Law School Library :: Free the Law – Overview

Harvard Law School Library :: Free the Law – Overview http://etseq.law.harvard.edu/2015/10/free-the-law-overview/

Summary of the 9/13/14 Legal Citation Hackathon includes links to outcomes and sources. There are a number of interesting things including using the Fastcase API.

Legal Citation Hackathon, 13 September 2014: Results, storify, links, and resources | Legal Informatics Blog :: http://legalinformatics.wordpress.com/2014/09/14/legal-citation-hackathon-13-september-2014-results-storify-links-and-resources/

What Free and Open Access To The Law Looks Like

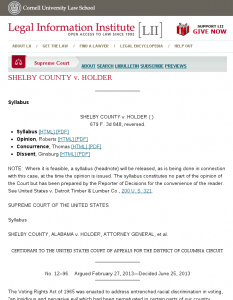

I spend a lot of time working on and thinking about free and open access to the law, mostly court opinions. Today1» the Supreme Court of the United States handed down a decision in Shelby County v. Holder. The opinion strikes down a section of the Voting Rights Act and will certainly trigger much discussion, debate, and possibly legislation going forward.

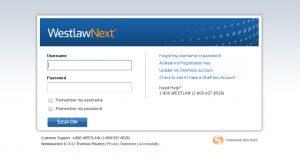

I’ll leave analysis of the decision to others and instead point out a graphic demonstration of the power of free and open access to the law. I think we can all agree that Shelby is going to have an impact on voting in America. Now this decision is the law of the land. Everyone needs to know about it. Access to the decision needs to be free and open. As soon as the opinion was issued it began cropping up on the web. Links were being posted to Twitter:

SHELBY COUNTY v HOLDER, now on #Westlaw 2013WL3184629 #SCOTUS #VRA http://t.co/ISt5Fy6iFL

— Thomson Reuters Westlaw (@Westlaw) June 25, 2013

Supreme Court decides SHELBY COUNTY, AL v. HOLDER, ATT'Y GEN., ET AL.. Decided 06/25/2013 http://t.co/x83NL5JopH #SCOTUS

— LII @ Cornell Law (@LIICornell) June 25, 2013

Following the links in these tweets provided interesting results that provide a graphic highlight of what free and open access to the law looks like. Clicking on the link in the Westlaw tweet gives the user this:

On the other hand clicking on the link in the LII tweet gets us to a better place:

On the other hand clicking on the link in the LII tweet gets us to a better place:

I understand that WestlawNext is a commercial service owned and operated by Thomson Reuters, but this document is law that applies to everyone in the United States. If you are going to link to it in a public space at least put the text of the opinion in from of the paywall so everyone seeing your link can read the opinion. Save the login for all of the extra value your products bring to the analysis of the decision.

I also understand that all too frequently our access to the law that governs our country is restricted by commercial interests who have little or no incentive to freely and openly distribute the law. Our law protects our freedom and our law needs to be free2» and open for all to readily access.

An Open Legal Taxonomy: It Just Starts With A List of Words

Lately I’ve been spending a fair amount of time thinking about taxonomies (and probably ontologies too, but I leave that distinction for another day) and their application to the various CALI and free law projects I work on. CALI maintains its own taxonomy for describing legal education materials. We call it the CALI Topic Grids or just Topics. Originally developed as away to guide our authors as they created CALI Lessons, the Topics were intended to identify what a professor wants to teach today. The level of specificity of a Topic is what is the point of a law to be covered in a particular classroom session. Like so many of our other resources the Topics are created by faculty teaching in the area covered by the Topics.

Now reaching beyond Lessons we use the Topics to describe podcasts, blog posts, crossword puzzles, chapters and sections of books, and most recently, court opinions. Like any good taxonomy Topics not only provide a useful way to describe the contents of a resource but also provide a useful finding aid. Indeed the Topics are best expressed as an outline, instantly recognizable to law students and faculty. The Topics serve as the headings for the outline with various resources gathered beneath, see for example http://topics.cali.org/contracts/.

As the free law movement in the US grows one of the most pressing questions that arises is how to categorize and describe the immense body of law. Simple full text searching and basic gathering of meta data about the law is easy enough to accomplish, but all that doesn’t tell us what the law is about. How do I know if a court opinion deals with the formation of a contract or some obscure point of criminal procedure? The short answer is that unless you are using a very large commercial legal data service that includes the use of topics and headnotes in its products you don’t know what the opinion is really about without reading it. Sure you may have a clue from the search that turned up the document, but that isn’t really a lot of reliable data. You need to have that opinion tagged with a known taxonomy.

Applying a taxonomy to law seems like a daunting task, but not as impossible as it once was. Once upon a time the idea of applying a taxonomy to the law in the US was pretty much a non-starter because you couldn’t get access to the law you wanted to categorize. The good news is that we’ve gotten past much of that. We now have access to sizable portions of the law in the US, at least enough to begin applying a taxonomy. Which leads us to the question of the taxonomy itself. How do we do that?

The worlds of taxonomy and ontology (again, I know the 2 are different, but I’m lumping them together here for arguments sake) are awash in a sea of acronyms and competing standards. Most of that stuff is really about the application of a taxonomy or ontology in a given situation, more about the “how” of describing things. That isn’t the main problem. The main issue is words. At their base taxonomies or ontologies are just lists of words. Carefully chosen, domain specific words, but still a list of words. And once you have the words, then you can apply them as you wish.

The creation of a list of words intended to describe the law has been done. Some lists are proprietary and unavailable to the free law movement. Other lists may be too general, more for describing broader collections not individual resources. There is one list, the CALI Topics, that describes specific points of law in individual resources. I would recommend using the CALI Topics as a starting point for creating an open legal taxonomy.

The CALI Topics are not an exhaustive list but with 41 top level topics and 14 published full Topic Grids they are a good start. The Topics can be expanded to include more top level areas of the law and complete Topic Grids can be added to make the Topics more comprehensive. Because the Topics exist as just lists of words they can be adapted to just abut any taxonomy/ontology framework/specification.

By using an existing taxonomy as a base, the free law movement can save a considerable amount of time and effort in getting started on the task of describing the law. The resources saved by adopting an existing taxonomy can then be applied to really hard problem of actually figuring out how to apply specific terms to a given resource. I have some ideas for that too, but I leave those for another post.

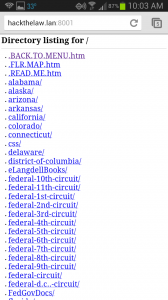

Hackthelaw: Piratebox meets Free Law

There are few “down” times in the CALIverse, but the Christmas through New Year holiday break is one of them. I use the time to do updates and upgrades and installs that would be disruptive at other times of the year. I also use the quiet stretches to try out new things. One of the new things I took a shot at this break is building a PirateBox. A PirateBox is:

Inspired by pirate radio and the free culture movements, PirateBox utilizes Free, Libre and Open Source software (FLOSS) to create mobile wireless communications and file sharing networks where users can anonymously chat and share images, video, audio, documents, and other digital content.

I grabbed an old Asus Eee PC net book that runs Debian Linux and followed the instructions on the wiki. The setup was pretty straightforward, but it is important to remember that you are disconnecting the wireless on the pc from the Internet and using it to create an access point of its own so once you launch the PirateBox script you no longer have Internet access via wireless. I decided to call my version hackthelaw.

I grabbed an old Asus Eee PC net book that runs Debian Linux and followed the instructions on the wiki. The setup was pretty straightforward, but it is important to remember that you are disconnecting the wireless on the pc from the Internet and using it to create an access point of its own so once you launch the PirateBox script you no longer have Internet access via wireless. I decided to call my version hackthelaw.

Once I had it up and running there was the matter of content. As it happens I have a lot of free law laying around (occupational hazard). I was casting about for a USB thumb drive to load stuff onto when I remember the great Free Law Reporter thumb drive that we did for CALIcon11. It contains LOTS of court opinions in EPUB format and seemed like a perfect starting point for downloads. I took one of the FLR drives and added all of the eLangdell ebooks (all formats), some choice gov docs from FDsys including the US Code, and the EPUB version of the Delaware state code. I plugged this into hackthelaw and had a very nice collection of law that could be downloaded to anyone who connects to hackthelaw.

If you’re still with me, you’re probably asking yourself, “So, what does all this mean to me?” Well, that’s a good question. The hackthelaw box is an open, anonymous network stocked with primary and secondary legal materials that are freely available for download. People can connect to the network and download any of the materials as well as chat with others connected to the network. All this is in a closed network space separate from the Internet. I can easily imagine setting this up in a library as a way for folks to access legal materials and even ask basic questions about the resources. Any device that has WiFi can connect to the network, so folks could download materials directly to their phones or tablets as well as laptops. Consider hackthelaw as another Free Law access point.

Beyond being a distribution node for Free Law, devices like hackthelaw have potential uses in legal education and practice. A closed private network could be used to distribute and receive law school exams. A professor could launch a network at the beginning of a class to provide students with that day’s material. In practice such a device could be used for gather initial client intake information. In conferences or negotiations a private network could handle the exchange of documents between parties. There are lots of possibilities here, and, as time becomes available, I hope to be looking into some of them in the not too distant future.

If you’re interested, I’ll be running some sort of hackthelaw device at the CALI booth in the AALS exhibit hall in New Orleans, January 4 -6, 2013.